By Peter M. Kenny

for The Magazine Antiques

January 2006

This installation marks the start of an ambitious five-year master plan for the renovation and renewal of many of the galleries and period rooms in the departments of American paintings and sculpture and American decorative arts.

For a loan exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 1934, Joseph Downs, the curator of the American Wing, brought together furniture and accessories from early colonial New York. In so doing, he acquired for the museum a rare gumwood paneled fireplace wall from a stone house in High Falls in Ulster County, dated 1752. Immediately after the show this paneling was incorporated permanently into the third floor of the American Wing (Fig. 1), where it became known as the New York Alcove and ever since has been home to an evolving display of late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century New York furniture. Downs wrote somewhat wistfully in the exhibition catalogue that the woodwork showed some “French provincial influence introduced by Huguenot settlers” in that region.1 He later amended this opinion, stating that it had features “more familiar” in “eighteenth-century American architecture,” by which he meant, of course, that it resembled English Georgian style paneling.2

View of the principal room

Pl. I

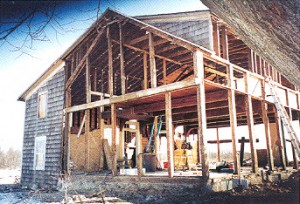

Despite its quality and great rarity as an example of mid eighteenth-century English style architectural woodwork from rural New York, the New York Alcove revels little about the building traditions of the Dutch and others of Low Country descent who settled the Hudson River valley. Current American Wing curators were acutely aware of this gap in the architectural presentation and sought alternative ways, none of them especially satisfactory, to make the alcove more architecturally representative of New York Dutch culture.3 The fates intervened in late 2002 when the opportunity arose to purchase an eighteenth-century house in the Albany region that was relatively pure New York Dutch design.4 Acquired without delay, the house was disassembled in the winter of 2003 with each step painstakingly documented, and then was kept in storage until March 2005, when installation of its principal room began on the third floor of the American Wing.

View through principal doorway

Pl II

This installation marks the start of an ambitious five-year master plan for the renovation and renewal of many of the galleries and period rooms in the departments of American paintings and sculpture and American decorative arts. Periodic reports on the progress of these projects will appear in The Magazine Antiques.

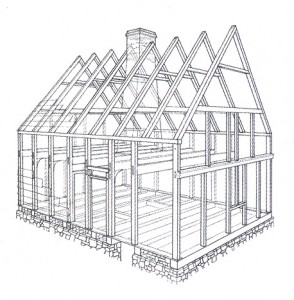

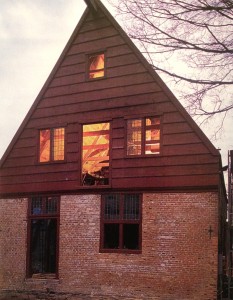

The old house, or what remained of it, was hidden in plain sight, standing anonymously in a sixteen-acre field in Bethlehem, five miles south of Albany. Known to only a handful of local residents as the “old Winne place,” even fewer people were aware that under later additions and alterations to the original steep gable roof was an eighteenth-century house frame of a distinctive type built by the earliest carpenters in New Netherland (see Pl III and Figs. 2, 3).5

Pl III

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Upon entering the principal room of the house through a decrepit lean-to addition on the blustery New Year’s Eve of 2002, my colleague Morrison H. Heckscher and I realized that it was a truly special interior that would offer museum visitors a first-class architectural experience. We felt it would become a wonderfully atmospheric gallery for the display of the American Wing’s rich collection of objects associated with early New York Dutch culture (see Pls. V, VI, VIa). Archaeological investigation, scientific analysis, and genealogical and historical research were all brought to bear in an effort to maximize our understanding of the house and its historical context.

Pl. V

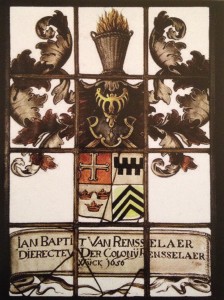

The sturdy timber-framed farmhouse was originally the home of a tenant farmer on the manor of Rensselaerswyck, an enormous estate surrounding the city of Albany. The manor was established by a charter in 1629 from the Dutch West India Company, which empowered the first patroon, Kiliaen Van Rensselaer (1595-1646), to purchase all the land beginning above and below Fort Orange on both sides of the [Hudson] river with the islands therein as many leagues downwards as the Assembly of the XIX has determined.6

For generations the Van Rensselaers administered their estate from houses of the same basic design as those occupied by their tenants until Stephen Van Rensselaer II, fifth patroon, built a grand English Palladian style house, which was completed in 1769.7 The large entrance hall from that house (Pl VIII) was acquired by the museum in 1928 and is now the pride of the American Wing’s eighteenth-century period rooms. It stands just a few feet from a room once occupied by a family that paid the Van Rensselaers a feudal style annual tribute of several bushels of wheat, a couple of fat fowls, and one day’s labor at a project of the landlord’s choosing.8

Pl. IX

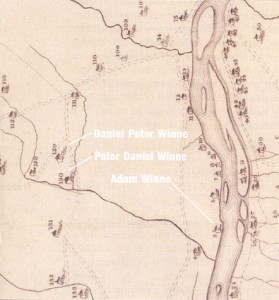

The original owner of the farmhouse, as recorded on the 1767 map of the estate shown in Plate IX, was Daniel Peter Winne, a fourth generation descendant of Pierter Winne (baptized c. 1609-d.c. 1692), known as Pieter the Fleming, who was born in Ghent in the province of Flanders (East Flanders in modern Belgium) and came to Rensselarswyck by way of Curaçao in 1652.

Daniel Winne’s house was located on the north side of a narrow creek that meanders eastward from the foothills of the Heldeberg Mountains to the Hudson. The stream derived its name, Vlaaman’s Kil (Fleming’s Kill), or Vloman Kill, from Pieter the Fleming, who first leased a sawmill near its mouth in 1652 and acquired it outright from the director of Rensselaerswyck, Nicholas Van Rensselaer (1636-1678), in 1677.9 The stream is close to the house of Daniel Winne’s father, “Old Peter Winne,” which was built about 1725 and has been undergoing restoration by its current owner since 2000 (Pl. IX, X).10

Fig. 4

Although built a generation apart, the houses of the father and son are almost identical in plan and construction, down to the exposed molded beans in the overhanging gable. The most obvious difference between the two is the exterior brick cladding on the first floor of the front gable and of the father’s house as opposed to the overall covering of the wide white pine clapboards on the side walls and on the back gable ends. These houses are the only known one-and-one-half-story timber-framed houses with overhanging gables in the Hudson River valley. Roderic H. Blackburn has suggested that the house with the brick gable end was an urban type built in a country setting, and cites for comparison an Albany example of similar design of about 1734, now demolished but known from a Historic American Buildings Survey photograph (Fig. 4). It once stood at 922 Broadway in Albany.11

A possible seventeenth-century design source for the overhanging gable may be village houses in the Zaan region of the province of North Holland, just north of Amsterdam. The Dutch architectural historian Jaa Schipper has published several views of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century wooden houses with overhanging gables covered with vertical weatherboards in the villages of Jisp and Assenfieldt.12

A house described in a 1659 contract at Beverwyck (Albany) for a timber-framed house “built up [partially faced] with brick” having a “gable of matched boards” may also describe a similar structure.13 Vertically oriented, overlapping, riven-oak boards are used on the back of the late seventeenth- or early eighteenth -century painted kast of simple board construction shown in Plate VI (see also Pl. VIa). It is probably the work of a carpenter and may offer a visual reference to a type of clapboards used on some of the earliest houses in New Netherland.

Pl. VIa

Veneered with bricks secured to the frame with iron wall ties elegantly wrought in the shape of fleurs-de-lis (see Pls. X, XI), or covered with clapboards, shingles, or a combination of both, New York Dutch timber-framed houses relied on one essential building component–the H-shaped anchor bent. Each anchor bent was comprised of two vertical posts, a heavy crossbeam and, where applicable, two corbels or corner braces (see Fig. 3). This method of building timber frames was very different from that used in England, or New England for that matter, which entailed more parts and joints as well as a multitude of neighbors and friends to help raise large sections of wall that were assembled flat on the ground.14 Dutch style anchor-bent house frames were much simpler in concept and easier to erect, with only three or four carpenters required to set them up on the foundation. The total number of bents and their spacing determined the length of the house, while the overall length of the anchor beams determined the width. A house with four or five anchor bents would usually be composed of one room with a garret above, while an eight to ten anchor-bent house would have at least two rooms and a correspondingly larger garret. The Daniel Peter Winne house has eight bents, and is twenty-two-and-one-half feet wide by just under thirty-three feet long. Descriptions of this type of construction are recorded in seventeenth-century house contracts in New Amsterdam (Manhattan) and Beverwyck. One contract of 1646 for a house to be built in or around New Amsterdam describes a six-bent house in which the carpenter Reynier Dominicus agrees to build and erect at his own expense for Cornelis van Tienhoven a house, 30 feet long on the inside, 20 feet wide on the inside, having on one side an aisle 8 feet wide, right through; the story in the fore part of the house to be 9 1/2 feet high and in the rear part of the house 12 feet high, consisting of five bents with corbels and one without; purlins and posts as required for the building; strong split rafters for the entire roof frame of the house and the roof frame to be tied with collar beams; the framework belonging to the chimney; in the fore part of the house a door casing with two lights and a door; a casement window with two blinds; in the partition a door frame and a door; in the rear a door frame with two lights, a bedstead in the aisle; the beams 10 inches high and seven inches thick. Reynier Dominicus to deliver all the square timber needed for the house and everything being well hewed and planed must erect it where required.15

A contract between Juriaen Hendricksen and his client Adriaen Dircksen Coen in 1649 describes an eight-bent structure in the vicinity of New Amsterdam forty feet in length and twenty feet in width, with one side an extension, six feet wide as long as the house is; six beams with corbels and two without corbels; six cellar beams; the posts as required, twelve feet long; four window frames with intersecting transom and mullion, two door frames and one suitable cellar door; the front room eleven feet high and the upper room nine feet, and the roof to be properly covered with tiles or reed.16

View of Van Rensselaer Hall

Pl. VIII

Except for the addition of side aisles, these agreements were worded much as they would have been between Daniel Peter Winne and the unknown carpenter who built his house, which was constructed more than a hundred years later in the spring or summer of 1751.17

The traditional Dutch architectural features that were originally part of the Daniel Peter Winne house included: tall single and double casement windows; a jambless fireplace with a large smoke hood; and two-part entry doors, commonly called Dutch doors, in both the front and back rooms. The exterior frame of the door into the principal room has a handsome cornice consisting of a large cyma reversa over two flat fillets molded directly on the thick horizontal framing member below the transom lights

Pl. IV

The Swedish naturalist Peter Kalm (1716-1779) offered the following comment on the fireplaces he had seen in houses north of Albany in 1749-1750: “The fireplaces among the Dutch were always built in, so that nothing projected out, and it looked as though they made a fire against the wall itself.”18 In the Winne house a brick wall divided the structure in two and served as the back wall of the fireplace, precisely as described by Kalm.19 A cast-iron fireback propped against it would have radiated heat back into the room and protected its plastered and whitewashed surface from being scorched. Like nearby all jambless fireplaces, it allowed as much heat as smoke to escape up the chimney and was later replaced with a more efficient English style fireplace with a smaller firebox and hearth. The replacement was made in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, but when the house was disassembled it was removed, revealing fragments of some of the original eight-inch-square red earthenware tiles, as well as a shard of an original blue-and-white imported Dutch tile with a biblical scene (see Pl. IV). These two features as well as a smoke hood and cornice have been reproduced in the new installation and provide an accurate image of the original fireplace.

Sadly, the original Dutch doors, casement windows and shutters, and the staircase in the principal room were removed long before the museum acquired the house. Ample evidence was discovered on the wood used for the framing of the precise locations and sizes of doors, windows, and shutters, and the missing staircase. However, given the almost total absence of original house parts incorporated in later additions, a certain amount of license was necessary in reproducing the missing elements. The abiding principle that guided the selection of replacement parts was that they had to be based on extant originals in eighteenth-century Dutch style buildings located as close to the Winne house as possible. The divided Dutch door at the main entry and the casement windows are based on surviving examples in the Tuenise Slingerland house of about 1762, which is in the town of Feura Bush in Albany County, several miles west of the Winne house site. The shutters are copied from a surviving example in the New York State Museum in Albany that is from a house of about 1740 in Defreestville in nearby Rensselaer County. The bold baroque mantel cornice, very similar in scale and profile to those on eighteenth-century kasten, is a replica of one found in the Mabee House of about 1725 at Rotterdam Junction in Schenectady County.

Pl. X

The staircase has not been duplicated. The scraps of evidence of the original stairs have proved inconclusive when compared to extant period staircases. They consist of a short run of stair treads that led from a landing to the second floor; a single board with a molded edge that was once part of the box that enclosed the open space beneath the stairs, and a charred piece of board that may have been a stringer cap. They were recovered in later additions to the house.

Despite the considerable losses over the years, the Winne house had good bones: an expressive framework of smoothly planed anchor beams, corbels, and ceilings–all with the undisturbed patina deposited by more than 250 years of exposure to light, air, and wood smoke. These elements are what make the restored interior of the Winne house so attractive and redolent of New York Dutch design.

According to the architectural historian Clifford W. Zink, exposed anchor beams and their handsomely curved corbels expressed a tradition-bound “structural logic” that was valued by the new world Dutch in their houses for a hundred years after the takeover of New Netherland by the English in 1664.20 This “logic” is apparent in the previously mentioned 1646 contract that required the carpenter Reynier Dominicus to deliver” all the square timber for the house…well hewed and planed.” In the well-ordered world of the seventeenth-century Dutch, anything less may have been an affront to the senses and a blot on the character of the household. Theirs was elegantly simple and direct style expressive of the care and orderliness of the minds that conceived the buildings and the carpenters who raised them.21

The new installation will include an exhibit mounted just outside the main entrance to the room explaining the distinctive character of New York Dutch timber-framed houses, and an interpretive program that will focus on the interrelationship between the Winnes and the Van Rensselaers over the course of seven generations, given that rooms from both the manor house and the home of one of their tenants are now in the American Wing. Visitors will have the opportunity to compare New York Dutch style buildings to the box-framed houses of New England by touring two adjacent and superb examples of the latter–the Thomas Hart (1611-1674) Room of about 1634 to 1674 from Ipswich, Massachusetts, and the John Wentworth (1671-1730) Room of 1695-1700 from Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The planned architectural display will include a deconstructed section of an actual post, beam, and corbel from the Winne house, as well as hand-wrought iron wall ties, shutter dogs, and other architectural metalwork from Hudson Valley Dutch houses (see Pl. XI).

The history of the Winne family at Rensselaerswyck has been richly detailed in reports prepared by Peter Christoph of the New York Historical Manuscripts Project, as well as in an article by Christoph, his wife Florence A. Christoph, and Floyd R. Brewer, an archaeologist.22 Their research revealed that Pieter Winne the Fleming from Ghent married Tanneke Adams, from Leeuwarden in the province of Friesland in the Neterhlands, in Rensselaerswyck about 1653, and that they had twelve children. This alliance of Flemish and Dutch represents precisely the blend of Low Country people that comprised a high percentage of the original settlers in New Netherland and today go under the rubric of the New York Dutch, according to the historian David Steven Cohen.23

Pieter the Fleming was energetic, honest, and able, which no doubht made him a favored tenant of the Van Rensselaers. At rensselaerswyck he was a farmer, a fur trader, a sawmill owner, and possible a carpenter.24 His public service included a stint on the “rattle watch” at Beverwyck in 1659 looking out for fires or suspicious activities from ten in the evening until four in the morning, and five two-year terms as a magistrate at Rensselaerswyck between 1672 and 1690, appointed by various New York colonial governors.25 Of Pieter the Fleming, Christoph writes: Numerically, there were few who stood higher in society (and none, save the occasional governor, who were absolutely separated by class), and many (including small farmers, common laborers and peddlers) who stood lower.26

Portait of Adam Winne

Pl. VII

Daniel Winne was descended from Pieter the Fleming’s youngest son, Daniel Pietersz Winne (c. 1675-1757), who was still a minor when his father died, and thus his interest in the estate was overseen by his “tutor,” Kiliaen Van Rensselaer.27 This early relationship with the patroon served him well throughout his lifetime. By the terms of Pieter the Fleming’s will Daniel Pietersz inherited the sawmill on Vloman Kill and the nearby farmstead at Bethlehem on the west bank of the Hudson River. Later, in 1711, Kiliaen Van Rensselaer granted him additional land along the stream.28 Upon his death, Daniel Pietersz left the sawmill and farmstead (see Pl. IX) to his second youngest son, Adam, whose portrait is shown in Plate VII. Prior to his death he also provided his eldest son, Peter Daniel, with some of the land along the stream that had been granted to him by Kiliaen Van Renssealer. Here Peter Daniel built his house about 1725 (Pl. X), five years after his marriage to Rachel Van Alen (baptized 1700). Like his father, he settled his eldest son, Daniel Peter, on farmland along the Vloman Kill about a half mile more to the west. Daniel Peter followed a similar pattern and built his house, in many ways a carbon copy of his father’s, about six years after his marriage to Jannetje de Forest in 1744. Their descendants lived at the farmstead until 1954,when it was sold out of the family.

Expanding on this multigenerational story of the Winnes at Rensselaerswyck will be a major thrust of the educational and interpretive programs centered on the new installation.

I would like to acknowledge Michael Kelley of J.M. Kelley Limited, Historic Architecture and Interiors, and his associates as well as Marijn Manuels and Rian Deurenberg of the objects conservation department at the Metropolitan Museum for their excellent work on this installation of the Winne house interior.

1 Joseph Downs and Ruth Ralston, A Loan Exhibition of New York State Furniture with Contemporary Accessories (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1934), No. 49, p. 6.

2 Quoted in Richard Townley Haines Halsey and Charles O. Cornelius, A Handbook of The American Wing, ed. Joseph Downs, 7th ed. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1942), p. 91.

3 The New York Alcove paneling came from a typical one-and-a-half-story Ulster County stone house with massive exposed beams on the first floor as wide as the house. As currently installed the wall paneling is reduced approximately seven feet in width. Reproducing the missing paneling, beams, and wood ceiling was considered but eventually ruled out as unfeasible.

4 The house was brought to the attention of the American Wing by the antiques dealer Jonathan Trace.

5 For the discover of the Winne house see Anne Miller, “Sleuthing Reveals a Dutch Master,” Albany Times Union, March 5, 20903, p. B1. The articles is available at www.timesunion.com.

6 Quoted in Samuel George Nissenson, The Patroon’s Domain (1937; reprint Octagon Books New York, 1973), p. 28. For more on Rensselaerswyck see

www.nysm.nysed.gov/albany/na/rensselaerswyck.html.

7 For two earlier Van Rensselaer houses in the New York Dutch style, Watervliet and Crailo, see Helen Wilkinson Reynolds, Dutch Houses in the Hudson Valley before 1776 (Payson and Clarke and Holland Soceity of New York, New York, 1929). Additional information on the original patroon’s house at Beverwyck can be found in Janny Venema, Beverwijck: A Dutch Village on the American Frontier, 1652-1664 (Verloren, Hilversum, Netherlands, and State University of New York Press, Albany, 2003), pp. 83-84 and pp. 210-214. For more on Crailo, see Shirley W. Dunn, “Settlement Patterns in Rensselaersijck: Crailo at Greenbush,” de Halve Maen, Magazine of the Dutch Colonial Period in America, vol. 75 (Fall 2002), pp. 49-56.

8 Peter R. Christoph, “Daniel Peter Winne, 1720-1800, 4th Generation,” report submitted to Peter M. Kenny, Metropolitan Museum of Art, August 26, 2003, p. 1, curatorial files, department of American decorative arts, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

9 Peter R. Christoph, “Pieter Winne the Fleming,” report submitted to Peter M. Kenny, Metropolitan Museum of Art, July 7, 2003, pp. 2 and 3, ibid.

10 Roderic H. Blackburn, “The Peter Winne House at Bethlehem, New York: A Site Report,” Dutch Barn Preservation Society Newsletter, vol. 12 (Fall 1999), pp. 1-7.

11 Ibid, p. 2. Blackburn illustrates a different, undated photograph of the house on p. 1. In 1676 a local ordinance at Albany mandated the size and materials of houses as follows: “All new buildings fronting in the street shall be substantial dwelling houses, not less than two rooms deep and note less than eighteen feet wide, being built in the front of brick and quarry stone and covered with tiles” (quoted in Clifford W. Zink, “Dutch Framed Houses in New York and New Jersey,” Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 22 [Winter 1987], pp. 280-281).

12 North Holland houses with overhanging gables are illustrated in Jaap Schipper, “Rural Architecture: The Zaan Region of the Province of North Holland” in New World Dutch Studies, Dutch Arts and Culture in Colonial America, 1609-1776, ed. Roderic H. Blackburn and Nancy A. Kelley (Albany Institute of History and Art, 1987), pp. 173-175.

13 Venema, Beverwijck, p. 441.

14 Schipper, “Rural Architecture,” p. 175.

15 Quote in Henk J. Zantkuyl, “The New Netherland Town House: How and Why it Works,” in New World Dutch Studies, Dutch Arts and Culture in Colonial America, 1609-1776, pp. 151-152.

16 Quoted ibid, p. 156.

17 Edward R. Cook and William J. Callahan, “Tree-Ring Dating of the Dismantled Timbers of the Daniel Pieter Winne House, Bethlehem, New York, January, 2004,” in Hartgen Archeological Associates, “Report on the Archeological Investigation of the Daniel P. Winne House,” submitted to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, March 2004, pp. 4, 7. Curatorial files, department of American decorative arts. Dendrochronology (counting the growth rings) performed on the oak cellar joists and hearth supports indicated that in six out of the nine samples the trees from which the parts were hewn were felled in 1750, in the autumn or winter when the growth season had ended. Three joists were cut earlier, one in 1747, one in 1748, and one in 1718.

18 Quoted in Roderic H. Blackburn, Dutch Colonial Homes in America (Rizzoli, New York, 2002), p. 43.

19 The America of 1750: Peter Kalm’s Travels in North America, trans. and ed. Adolph B. Benson, rev. ed. (Dover Publications, New York, 1966), vol. 1, p. 356. The only completely intact surviving eighteenth-century example is in the Jean Hasbrouck House in New Paltz, New York.

20 Zink, “Dutch Frames Houses,” p. 272.

21 Jeremias Van Rensselaer (1632-1674) emphasized the significance Dutch colonists placed on anchor beams. Referring to his new house, Van Rensselaer stated in 1666, “as to the joists being too heavy, I never heard any one say so, except that one beam, which lies before the chimney, is a very thick and heavy timber. And they ought not to be much thinner, for owing to the extra width of the house all depends on the joists, which have no corbels to stiffen them…the chamber story also has good beams, not too heavy, and of dressed lumber, free from knots” (quoted ibid., p. 283).

22 Peter R. Christoph was commissioned to research the lives of Daniel Peter Winne (1720-1800), his ancestors, and his descendants (see notes 8, 9, and 27). See also Foyd I. Brewer, Florence A. Christoph, and Peter R. Christoph, “Three Centuries at a Winne Family Farmstead: an Interdisciplinary Study,” de Halve Maen, vol. 75 (Fall 2002), pp. 42-49.

23 David Steven Cohen, “How Dutch Were the Dutch of New Netherland?,” New York History, vol. 62 (1981), pp. 43-60.

24 Christoph, “Pieter Winn the Fleming.” On September 26, 1658, Pieter The Fleming was paid five guilders for making a crib for a sick person, and in June 1670 he was paid for carting a piece of wood for the gutters on the poorhouse (Deacon’s Accounts 165201674, First Dutch Reformed Church of Beverwyck/Albany, New York, ed. and trans. Janny Venema [Picton Press, Rockport, Maine, and William Eerdman’s, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1998], pp. 53, 215).

25 Ibid., pp. 4 and 5 as quoted in Minutes of the Court of Fort Orange and Beverwyck, 1652-1660, ed. and trans Arnold J. F. Van Laer (University of the State of New York, Albany, [1923]), vol. 2, pp. 209-210; Minutes of the Court of Albany…, ed. and trans. by Van Laer (University of the State of New York, Albany, 1926-1932), vols. 1-3 passim; “Minutes of the Convention of Civil and Military Officers, Albany City and County, June 28, 1689-March 20, 1689/90” p. 101, Albany County Hall of Records.

26 Christoph, “Pieter Winne the Fleming.” p. 10.

27 Peter R. Christoph, “Daniel Pietersz Winne (c. 1675-1757), 2nd Generation,” report submitted to Peter M. Kenny, Metropolitan Museum of Art, August 26, 2003, p. 1, curatorial files, department of American decorative arts.

28 Ibid., p. 1. The Winnes, beginning most likely with Daniel Pietersz, held lifetime leases at Rensselaerswyck, which entitled the lessee to something very close to outright ownership and allowed him to divide the holding among his heirs. He was obligated to remit one quarter of the purchase price to the lord of the manor if he sold the land, and he owed a nominal annual payment in produce, livestock, and labor. See Christoph, “Daniel Peter Winne, 1720-1800, 4th Generation,” p. 1.

Peter M. Kenny is a curator in the department of American decorative arts and the administrator of the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.