Ned Depew

Berkshire Homestyle

May 2009

If you are a regular reader of this magazine, you may remember that we have been following-since 2005- the progress of an 18th century Dutch house from obscurity (and possible destruction) as a tenant house remodeled nearly into oblivion to international fame, as an exhibit in the new American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan.

For those who may have missed the earlier installments, our story so far: in an obscure corner of Bethlehem, an excavating contractor bought a piece of abandoned farm land to use as a storage site for his heavy equipment and stockpiles of materials. There was a small house on the property, typical of the area, cobbled together from various parts during various periods.

It had vinyl siding, a series of additions of wildly varying qualities of construction, a set of dormers and had been used as a rental for a number of years. The contractor was trying to decide whether to rehab it and try to rent it, or whether to just demolish it and take the tax savings for converting the property as “vacant land.”

He called on his lawyer, who had extensive real estate experience, for advice. The lawyer wanted to see the property, so the two men paid a visit to the now vacant house.

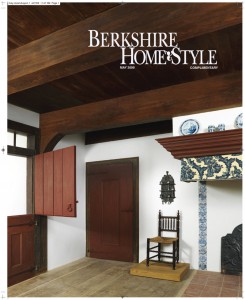

The lawyer was surprised and impressed by what he saw. The first floor of the original building was a large single room with a center chimney. Although the interior had been remodeled, overhead was a sight that surprised him, massive, polished carrying beams and ceiling (the bottom of the floor above) of polished chestnut.

Another of that particular lawyer’s clients was restoration and renovation specialist J. M. (Mike) Kelley and the lawyer had been on the sites of some of Kelley’s projects He didn’t know exactly what he was seeing, but he knew enough to suspect that it was something of interest. He advised his contractor client to get in touch with Kelley and arranged a meeting between the two men.

Kelley confirmed that the building was indeed a rare find, a very early Dutch farmhouse more or less encapsulated in layers of later building. He advised the owner to hold off on demolition while he made further inquiries.

Through his other work – for antiquarian Jonathan Trace– Kelley had contacts at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s (MMA) American Architecture Department. He made some phone calls, held a few conversations and then a few meetings at the site. He had his own opinion confirmed and established that the building was of interest to the MMA.

They had been planning a renovation of the American Wing including their period rooms and had felt the lack of an appropriate example of the earliest Dutch Period Architecture, both for its own sake and as a setting for their collection of art, furniture and household objects from that time. The main floor of the Winne House with its beautiful hand-hewn beams and polished ceiling filled the bill.

The next step was the dismantling, transportation and reassembling of the building. This was a job squarely in the area of Kelley’s expertise. So, in 2003, Kelley and his crew planned, photographed, labeled and annotated as, piece by piece, they dismantled the original structure. It was an exacting and demanding job, but with the support and advice of the museum staff, they reduced the building to a neat pile of timbers, boards and millwork, all neatly marked and ready for shipment on the bed of a tractor trailer to a facility where they could be cleaned, fumigated and temporarily stored. In Manhattan, the process was reversed. First the pieces had to be lifted by an eighty-foot crane to a window on the third floor of the building, which was removed to facilitate loading. Once the materials were all in place (a far more complicated and daring exploit than it sounds in a single sentence!), the long, careful process of reassembly began.

In 2005, as reported in a second article here, the job was completed, and that phase of the project finished. But, it was only the beginning of a closer and more intense connection between Kelley and the museum. Having established a comfortable working relationship on a collegial basis, both Kelley and the museum’s staff felt comfortable moving ahead with other projects, which occupied significant blocks of their time through the years.

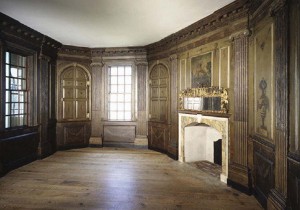

Among the most notable was the latest, the relocation of the “Marmion Room,” which was begun early in 2008 and just completed this winter. The late 18th century room was originally moved into The Met in 1924 and relocated during an earlier renovation in the 1970s. This was the most exacting of The Met projects Kelley has undertaken for a variety of reasons. In the first place, the room is asymmetrical, with seven sides and no right angles.

In the second place, all of the architectural detailing of molding, millwork and trim had to be reassembled to fit exactly as it had originally. But, as was typical of the period, the room had been built by “scribe rule” and to eye, rather than by measure and level, so the correspondance of the details could only be preserved by reference to the room itself, which, therefore, had to be mapped and documented with an extraordinary level of detail.

An added complication to this facet of the project was the fact, as discovered by Kelley and his crew in dismantling the room, that it had been re-worked before, probably in the century of its creation. Scribe marks on the backs of some of the panels and changes in the molding profiles (every 18th century carpenter made and sharpened his own molding planes to his own unique shapes) indicated that some of the trim work was a later addition.

In the third place, the wooden panels of the walls are all painted with decorative scenes and patterns, making exact matching essential. And, of course, the room had originally been built before it was painted, so the re-assembly would have to be so perfect that the paint-lines would correspond exactly.

One additional major obstacle to this process was the fact that the room had been moved within the museum during the 1970’s reconfiguration. At that somewhat less rigorous period, it had been altered to fit the location where it was installed, which had a floor that was distinctly out of level and uneven. To relocate the room without throwing the details out of register, Kelley and his crew had first to map the irregularities of the existing floor, using laser-level technology and then shim the dead-level floor of the new location to match.

Beyond that, the process was similar to that of the Winne House, but where the Winne House was relatively rough-hewn and fitted, the woodwork of the Marmion Room was delicate and exact. It was a time-consuming process requiring enormous attention to detail, as a few small fractions of an inch variation at one end of the construction could translate into significant deviation by the time it reached the other end. Although it wasn’t physically demanding, Kelley says, the need for constant minute attention to detail made it exhausting.

But it is finished, to Kelley’s and the curators; satisfaction, and with its completion, nineteen of the twenty rooms of the American Wing’s interiors are ready to go back on public display for the first time in years. On May 19th, the fruit of Kelley’s long labor for the Met will open to the public.

It will be a big step forward for The Met, as the re-opened American Wing is expected to be a big draw after years of closure and limited access. And the improvements that have been made will provide a showcase for the collection of distinctively American objects that will put them more clearly in context and make them more accessible as part of a whole way of life, rather than as isolated “exhibits.”

Peter Kenney is a curator at the museum and Administrator of the American Wing. He oversaw the Winne House project from the start and is enthusiastic about the opportunity its addition affords, to tell the story of the Dutch and other low country people who were the original European settlers in New York. The lack of such a setting was sorely felt, as the large collection of objects from this period were difficult to show effectively without appropriate architectural surroundings.

Kelley’s work has been good for the American Wing, Kenney acknowledges. Not only the Winne House, but also the numerous other projects Kelley and his crew have undertaken have helped realize the Museum’s goal of providing an authentic, wide-spectrum experience of American culture as expressed through architecture and artifacts, through the centuries.

And the work has been good for Kelley and his crew, as they have honed their skills on the exacting and demanding jobs and learned much about the history and development of the buildings in which they work. Working with museum staff, they’ve observed how professional historians and curators analyze and understand what architectural spaces have to tell us about our forebears and, ultimately, about ourselves. It has been an education in both directions as well, as Kelley’s understanding of antique construction techniques generated insight into why things were done the way they were.

The principle drawback to doing such prestigious work, Kelley says, is the impression that it can give some potential clients that their projects are somehow “beneath” him. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Kelley and his crew have done–and continue to do–a whole range of projects. The proposals clients bring to Kelley do involve historic restorations and some include the dismantling and re-assembly of vintage buildings. Those are areas in which the company has special expertise. But, within those parameters, Kelley has undertaken restoration of structures from every period from the 17th through the 20th centuries and in every style from early Dutch Colonial to 20th century Arts & Crafts.

Some projects involve reconfiguring the interior of vintage buildings to suit modern lifestyles, accommodate contemporary conveniences and mechanical systems and improve energy efficiency, while staying true to the buildings’ historical integrity and identity. Others are simply about the relocation of antique barns and homes from one location to another. Still others involve the use of the elements of vintage buildings to create spaces that serve functions completely different from their original use.

But whatever the project, they all have to be approached, says Kelley, with the same level of attention. “What we do isn’t a job,” Kelley avers, “it’s a life. I read about it. I think about it. When I go on vacation, I usually end up seeking out and visiting period homes and studying them. It’s what I do for a living, but it’s also what I do for fun. If we didn’t like the people we work for and the work we do, it would be a waste of time.” You can learn more about the work of Kelly and his crew at their website, www.jmkelleyltd.com or you can

email at Michael@jmkelleyltd.com.

You can see their handiwork at the American Wing of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.